Military Sexual Trauma: Why Accountability Is the Proven Solution

Military Sexual Trauma won't stop with awareness campaigns alone. In this episode of The Silenced Voices of MST, expert Chuck Derry, founder of The Gender Violence Institute, shares 40 years of research proving accountability is the only solution that works.

Chuck Derry, founder of The Gender Violence Institute, shares his extensive experience in addressing gender violence, offering insights into its cultural roots, the importance of accountability, and the personal reflections necessary for achieving true equality. This episode describes Derry's work and perspectives, providing a comprehensive overview of his approach to combating abuse and enacting cultural change.

Content Warning: This episode and article discuss gender violence, domestic violence, sexual assault, Military Sexual Trauma, abuse dynamics, and systemic failures in addressing violence. Please engage with this content when you feel safe and supported.

In episode 43 of The Silenced Voices of MST, Chuck Derry, founder of The Gender Violence Institute, shares his extensive experience in addressing gender violence, offering insights into its cultural roots, the importance of accountability, and the personal reflections necessary for fostering equality. He has worked to end men's violence against women since 1983 which resulted in co-founded the Gender Violence Institute in 1994. His decades of experience offer critical insights for those working to address Military Sexual Trauma, as the dynamics he documented in civilian domestic violence cases mirror what happens in military systems where sexual assault thrives.

Chuck Derry: 40 Years of Proven Gender Violence Prevention Research

Chuck Derry, with over 40 years of experience since 1983, discusses his transformative journey in gender violence intervention. Initially, he worked with feminist women to combat men's violence against women, an experience that profoundly shaped his understanding. Derry emphasizes that 95% of his knowledge comes from learning from women, while the remaining 5% is based on his experiences as a white male growing up in Minnesota, navigating sexist and racist societal norms. His approach centers on accountability, cultural change, and the willingness of individuals to examine their own complicity in systems that perpetuate violence.

How Gender Violence Begins: Cultural Roots of Violence Against Women

Initially, Derry reflects on his early experiences and realizations about gender dynamics. He recalls understanding at a young age that being a girl was considered the worst thing, influencing his behavior to align with perceived masculine ideals. He shares an anecdote from Catholic school where boys would expose girls' underwear. Adults saw it happen and did nothing. The message was clear that boys were more important than girls.

Derry points out that statistics show girls in the U.S. face a one in three chance of being beaten by a partner and a one in two chance of being sexually assaulted. These statistics are an unsettling reminder of the pervasive cultural issues that begin in childhood and continue throughout life. The normalization of disrespect and violence toward girls creates a foundation for the gender violence that persists in adulthood and globally across institutions, including the military.

Military Sexual Assault: How Military Culture Protects Perpetrators

The conversation shifts to the military, where values of honor and integrity coexist with significant problems of sexual assault. Rachelle shares a personal experience of sexual assault at a VFW, remembering how deeply ingrained cultural norms can override stated values. She notes that even when incidents are reported, varying definitions of consent among jurors in military courts can alter outcomes. Accountability must be consistently adhered to, rather than relying on subjective interpretations that often favor perpetrators.

The contradiction between military values and the reality of sexual assault rates is evidence of a structural problem. Systems that center male power often protect male violence. The burden falls on survivors to prove what happened, while perpetrators benefit from doubt, confusion, and institutional protection.

Proven Accountability Program: How the Duluth Model Changes Abusive Behavior

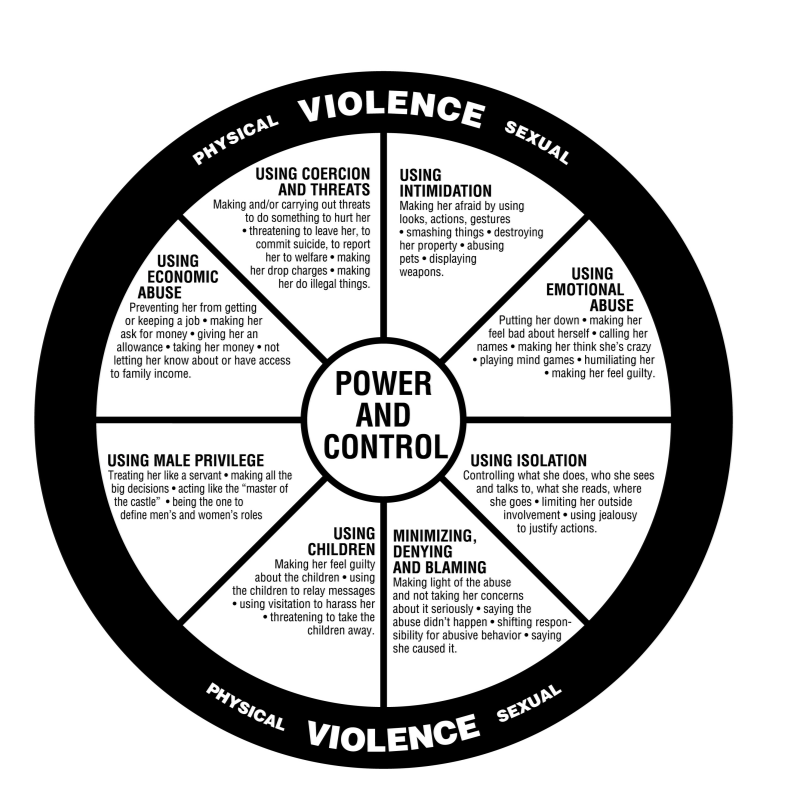

The 24-week program Chuck led was designed to address abusive behavior. Men ordered to participate must acknowledge their violence and understand the power and control dynamics involved. The program uses the Duluth Power and Control Wheel, requiring men to log instances of physical and emotional abuse, intimidation, and other controlling behaviors.

Battering is one form of domestic or intimate partner violence. It is characterized by the pattern of actions that an individual uses to intentionally control or dominate his intimate partner. That is why the words “power and control” are in the center of the wheel. A batterer systematically uses threats, intimidation, and coercion to instill fear in his partner. These behaviors are the spokes of the wheel. Physical and sexual violence holds it all together—this violence is the rim of the wheel. (Duluth Model)

The Duluth Model's Power and Control Wheel is a tool developed in the 1980s through focus groups with female survivors. Women compiled lists of the types of abuse most commonly used against them. The wheel helps survivors step back and see the full scope of violence they have experienced. It gives them language to name what happened. For many survivors, that validation changes everything.

Derry is careful to note that participants were initially resistant, often minimizing, denying, and blaming. However, the structured accountability led to significant changes. The consequences, enforced by the criminal justice system, probation officers, and community support, were essential to deterring abusive behavior.

Why Perpetrators Continue Violence: Understanding the Benefits of Abuse

One experience in particular stood out most in this program. Chuck Derry spent years sitting across from men who had been court-ordered into his program after harming their partners. He asked them to do something most had never done: list the benefits they got from their violence.

At first, they resisted. Then they filled a four-by-eight-foot blackboard.

The list included advantages such as maintaining control, gaining money, avoiding change, dictating reality, determining what values their kids would have, controlling where their partner went and who they talked to, and deciding when and how sex happened. The list went on for hours. This exercise, conducted in the 1980s and 90s as part of a structured accountability program in Minnesota, revealed something that survivors already knew but systems refused to acknowledge. Violence works for perpetrators until someone makes it stop.

These deep-seated reasons why men perpetuate abusive behavior, even if they themselves are not abusive. The difficulties in relinquishing these perceived benefits is what perpetuates “looking the other way” or not speaking up against it. Understanding these benefits is crucial for developing effective intervention strategies.

Military Sexual Trauma Prevention: Why Accountability Is the Missing Piece

Accountability is crucial in preventing MST. Consequences, enforced by the criminal justice system, probation officers, and community support, were essential to deterring abusive behavior in his program. He shares that men who were kicked out of the program for not taking responsibility often returned, admitting they could no longer get away with it.

The Pentagon nearly doubled its sexual assault prevention budget to more than $1 billion in 2023 and 2024. They established new offices to prosecute cases outside the traditional chain of command. They hired about 1,400 trained prevention specialists to serve at bases around the globe. However, while 8,195 sexual assaults were reported in 2024, independent research estimates the actual number may be 2-4 times higher. Dr. Jennifer Greenburg's research estimated approximately 73,695 cases of sexual assault in the military in 2023, nearly nine times the number of official reports.

The gap between what happens and what gets reported reveals everything about the lack of accountability. Derry's work identified the two factors most strongly associated with men who perpetrate violence: childhood experiences of abuse and witnessing violence, and attitudes related to gender equity. He also identified what keeps violence going: impunity. When perpetrators face no consequences, they have no reason to stop. The benefits outweigh the risks. The behavior continues because it works. Awareness campaigns and training modules alone cannot stop sexual assault. Accountability through consequences and other men speaking up and influencing other men stops it.

Gender Equality: What Men Must Sacrifice to End Violence Against Women

Derry reflects on the personal sacrifices required to achieve true equality. He questions whether men are willing to give up the benefits and privileges they receive in a sexist culture. This includes confronting male bonding over objectification, stopping the use of pornography, listening to women, and relinquishing leadership positions if necessary.

The list includes things men rarely talk about, such as male bonding over objectification, pornography use, dominating conversations, holding leadership positions they are not qualified for simply because they are men, controlling household decisions, and dictating when and how sex happens. The benefits of sexism are real, tangible, and daily.

Giving them up requires more than good intentions. It requires confronting how deeply those benefits are woven into identity, relationships, and career advancement. In military contexts, this means confronting how sexual violence functions as a tool of dominance and control, how it reinforces hierarchies, how it silences dissent, and how it maintains power structures that benefit some service members at the expense of others.

Derry challenges men to consider what kind of human being they want to be and whether they care about the lives of others. The ratio of learning from women versus his own experience matters, because it tells us who holds expertise, whose voices should lead prevention efforts, and why survivor-centered approaches work and top-down institutional responses fail.

How Military Sexual Trauma Survivors Can Demand Accountability

Chuck Derry's decades of work in gender violence intervention offers a clear roadmap for addressing Military Sexual Trauma. Violence works for perpetrators until someone makes it stop. Awareness campaigns, training modules, and billion-dollar budgets cannot replace genuine accountability. Systems must create and enforce real consequences for perpetrators while centering survivor voices and experiences.

For survivors of MST, your story holds expertise that no institutional training can replicate. Your insistence on accountability is not asking too much. You deserve justice, support, and systems that prioritize your safety over institutional reputation. The work of creating change requires all of us to examine our complicity in systems that protect perpetrators and to demand better from our military institutions.

Resources for Veterans Seeking Help

If you are a Military Sexual Trauma survivor, The Silenced Voices of MST offers several free resources and tools to support your journey:

VA Disability Toolkit: A free resource built to help you organize the VA claim process with tips and strategies from those who have successfully navigated the system. Document your trauma, track your claim, and organize every detail for a stronger case.

Contact Your Lawmaker Toolkit: Make your voice heard in Congress. This toolkit allows you to easily and safely contact members of Congress about MST-related legislation, military reform, or your personal experiences with templates and state-specific lookup.

The Advocates of MST Private Facebook Group: Join a safe, private community where survivors can connect, share experiences, and access peer support without fear of retaliation or judgment.

Crisis Support: If you are in crisis, please reach out:

Veterans Crisis Line: Call 988 and press 1, or text 838255

National Sexual Assault Hotline: 1-800-656-4673 (RAINN)

DoD Safe Helpline for Military Sexual Assault: 1-877-995-5247

Episode Chapters and Timestamps

00:00 Meet Chuck Derry, Founder of The Gender Violence Institute

03:48 Childhood Memories of Cultural Behavior Towards Girls and Women

05:49 Military Culture and Rachelle's SA at the VFW

10:15 The 24-Week Program That Successfully Changed Behavior

12:07 The Benefits of Abusive Behavior

16:01 The Missing Piece in Prevention of MST

17:54 Chuck's Reflections on Life if Equality Actually Happened

Frequently Asked Questions

-

The Duluth Model Power and Control Wheel is a tool developed in the 1980s through focus groups with female survivors of domestic violence. Women compiled lists of the types of abuse most commonly used against them. The wheel helps survivors understand the full scope of violence they have experienced by identifying patterns of physical violence, emotional abuse, intimidation, isolation, economic abuse, and other controlling behaviors. It gives survivors language to name what happened to them.

-

Perpetrators continue abusive behavior because it provides tangible benefits and they face no consequences. The benefits include maintaining control over others, gaining financial advantages, avoiding personal change, dictating reality in relationships, determining family values, controlling where partners go and who they talk to, and deciding when and how sex happens. When there is no accountability, the benefits outweigh any risks, so the behavior continues.

-

Cultural factors that contribute to gender violence include societal norms that devalue girls and women from childhood. Boys learn early that being a girl is considered inferior, which shapes attitudes and behaviors. Adult inaction when boys mistreat girls reinforces the message that boys matter more than girls. Statistics show that girls in the U.S. face a one in three chance of being beaten by a partner and a one in two chance of being sexually assaulted. These cultural patterns begin in childhood and persist throughout life.

-

Achieving gender equality would require men to give up significant benefits and privileges. This includes male bonding over objectification of women, pornography use, dominating conversations, holding leadership positions they are not qualified for simply because they are men, controlling household decisions, and dictating when and how sex happens. These benefits are woven into male identity, relationships, and career advancement. Giving them up requires more than good intentions. It requires confronting complicity in systems that perpetuate inequality.

-

Accountability is the crucial missing piece in preventing Military Sexual Trauma. Without real consequences for perpetrators, sexual assault continues because it serves the perpetrator's interests. Awareness campaigns and training programs alone cannot stop sexual assault. Systems must create meaningful consequences that are consistently enforced through the criminal justice system, command structures, and community support. When perpetrators face genuine accountability, they can no longer get away with their actions.

-

The gap between actual sexual assaults and reported cases in the military is significant. While 8,195 sexual assaults were reported in 2024, independent research estimates the actual number may be 2-4 times higher. Dr. Jennifer Greenburg's research estimated approximately 73,695 cases of sexual assault in the military in 2023, which is nearly nine times the number of official reports. This gap reveals the lack of accountability and trust in military reporting systems.

-

Survivors do not report for several reasons. Many want to forget about the assault and move on. They do not want more people to know what happened. They feel ashamed or embarrassed. Among servicewomen who did report, 38 percent experienced professional reprisal, 51 percent experienced ostracism, and 34 percent experienced maltreatment. The consequences of reporting fall on survivors rather than perpetrators, which discourages reporting.

-

Accountability programs can be effective when they require participants to acknowledge their violence, understand power and control dynamics, and face consistent consequences. The 24-week program that Chuck Derry helped develop required men to log instances of abuse and understand the Duluth Model. Initially, participants minimized, denied, and blamed. However, structured accountability enforced by the criminal justice system, probation officers, and community support led to significant behavioral changes. Men who were removed from the program for not taking responsibility often returned later, admitting they could no longer get away with their behavior.

-

The Gender Violence Institute was co-founded by Chuck Derry in 1994. The organization works to end gender violence through an approach that recognizes the connections between violence, power, and privilege. The Institute engages in community organizing, policy development, education, and training. Their work emphasizes that individual behavior change alone cannot end sexual assault. Systems and cultures must change, and consequences for perpetrators must be real and consistent.

-

Military culture contributes to sexual assault when stated values of honor and integrity coexist with systems that protect perpetrators. Deeply ingrained cultural norms can override stated values. Varying definitions of consent among jurors in military courts can alter outcomes. Systems that center male power often protect male violence. Sexual violence functions as a tool of dominance and control, reinforces hierarchies, silences dissent, and maintains power structures that benefit some service members at the expense of others.

About the Guest

Chuck Derry is the founder of The Gender Violence Institute. Since 1983, he has worked to end men's violence against women through accountability programs, community organizing, policy development, and education. His approach centers on understanding the cultural roots of gender violence and creating systems that hold perpetrators accountable while supporting survivors.

Help Support our Mission

This work saves lives. Every story shared, resource created, survivor connected to help. The Silenced Voices of MST exists because too many survivors have been silenced for too long. This work is necessary, but it cannot continue as a one person sacrifice. I am asking for your support to help transition this platform into a sustainable resource. If this mission matters to you, please consider making a donation or sharing this campaign with your network. Every episode produced, every toolkit distributed, every survivor story amplified requires resources. Production costs, hosting fees, website maintenance, and platform development all depend on the generosity of people who believe survivors deserve better.

Your donation directly funds:

Administrative Support: $12,000 to hire a part-time assistant. This is the only way to shift the twenty-person workload off of one individual and ensure the show’s longevity.

Operational Recovery: $8,500 to address the debt incurred by the show's operations since 2023. This is essential to stop the cycle of negative balances and financial instability from paying for the show with VA disability

Production & Security: $4,500 to cover the upcoming year of hosting, extra security features for guest safety, and necessary software subscriptions.

Thank you for standing with survivors.

About the Host

Rachelle Smith is an Air Force veteran, MST survivor, and the founder of The Silenced Voices of MST, an advocacy platform focused on Military Sexual Trauma. With a background in Communications and a distinguished career as a US Air Force Public Affairs Officer, Rachelle is committed to amplifying the voices of survivors and demanding accountability from institutions that have failed them.

After years of struggling in silence, Rachelle created The Silenced Voices of MST to help this long-ignored community document their truth, speak out, and fight for future service members. The platform offers the VA Disability Toolkit, the Contact Your Lawmaker Toolkit, guided trauma recovery journals, and leads The Advocates of MST, a private Facebook support group.

Through her podcast, Rachelle provides a safe space for MST survivors to share their stories, access resources, and find community. Her work centers on visibility, support, and accountability for Military Sexual Trauma survivors worldwide.

Connect with Rachelle: silencedvoicesmst.com | Email: info@silencedvoicesmst.com

-

Chuck Derry (00:00)

we first started working with batterers in 80s, we thought, oh, these guys just didn't have the life skills they need to address their emotions, or they lost control, And then we find out they'd use those life skills as a more sophisticated way to

And that's when we realized this is very conscious behavior. They know exactly what they're doing.

Chuck Derry with the Gender Violence Institute in Clearwater, Minnesota. I've been doing this work since 1983, 41 years. I was 27 when I started. And it was amazing. It transformed my I started working with feminist women to end men's violence against women and just blew me away.

And 95 % of what I share, I learn from women. as a guy, I'm always expected to be the % of what I share with you, learned from women. And the other 5 % is what I'll share about just being a white boy in Minnesota growing up and US and the sexist, racist stuff that.

was embedded into my bones.

Rachelle Smith (01:11)

Yeah, and unfortunately that's just a part of American culture and we got a long way to go in changing all of that. what were the things that came to pass in your life that led to starting this institute?

Chuck Derry (01:23)

Well, in my early 20s, I was doing roofing and carpentry. And my wife at the time got a job in St. Cloud at the women's shelter, battered women's shelter. And I knew carpentry wasn't quite what I wanted to do with my life. So I kind of put it up to the universe for what could happen next and show me a path and

we moved st cloud and a friend of some friends of mine started the St. Cloud Intervention Project which is based off intervention project and it was really getting criminal justice system to do something about men abusing women and part of that was guys would be arrested they have jail time over the head and then they have come twenty four week accountability groups and they were looking for somebody to facilitate these accountability groups

So I went in there and here's how high the bar was. This is 83. The guy before me, asked him, so what do you think about sexism? He said, sex, I like sex. Sex is good. So I knew what sexism was. That's how I got hired. Because I knew it's, that's how high the bar was. Because in the US, we're just starting to work with men who batter. and I thought, this would be interesting, but it totally transformed my

Rachelle Smith (02:22)

boy.

Chuck Derry (02:35)

started working in this feminist women's organization, I thought I was a pretty nice guy. didn't think I was very racist and stuff. And then I found out my big toe was sexist. It wasn't just this little attitude, it was bone deep. And so it's very amazing how much it challenged me about my male privilege. And then also challenged me about, I care about women's lives? What kind of human being do I wanna be? And then also working within the system, the male system.

To get them to actually arrest men who are beating and raping their wives and children. Because that wasn't happening. every lie I was told about girls and women, they're stupid, they're emotional, they're weak, was all revealed to me. doing this work. And it's just been amazing. I've worked with amazing women. And I've been a very, very lucky, man.

Rachelle Smith (03:19)

just, I can't imagine how sobering that must've been there's this entire, web or blanket or whatever you want to call it. That's thrown over men's eyes. to where they can't really see us as people, unfortunately.

Chuck Derry (03:37)

a, yeah, that's why it transformed my life. I was so lucky to be with women who would debate me.

about sexism, they'd argue with me, they'd even be willing to get angry with me rather than just blow me off.

I was just really lucky.

there's all kinds of stories I can tell about, okay, how this impacted how I with friends and towards girls and

what I grew up with.

Worst thing I'd be in first grade, was six years old. I realized I was going to a little Catholic school and then.

I realized the worst thing I could be is a girl.

throw a ball-like girl or a run-like Anything like a girl. That's how I knew I was the right kind of boy. I looked around my world in 60s. The men were in charge everywhere. so I'm six years old. Didn't take a rocket scientist to figure out if the worst thing I'd be as a girl, then boys are better than girls. ⁓ duh. And then how do we change our behavior with the girls when we thought we were better? And I'll give you one example. In second grade, I was in Catholic school.

and we had to wear uniforms. So the girls had to wear dresses down to their ankles and we had to wear ties. At recess, we'd run after the girls and we'd grab their dresses and we'd say, Tuesday, dress up day. And we'd throw their dresses up in the air so we could see their underwear. They had polka dots on their underwear or butterflies. Oh, we'd be rolling around on the ground laughing and they'd be going, get out of here, leave me alone. Which was part of the fun. the girls all started coming to school with culottes. What we called culottes in those days, they were shorts.

to school wearing shorts underneath their dresses because of what the boys are doing. And there were adults in that playground who had to have seen this and did nothing. As they just went, will be boys, boys are enjoying themselves, okay, they're more important than the girls, apparently. So, I mean,

The cultural stuff the stats I've seen is if you're born a girl child in US, you have a one in three chance of being beaten by the man you're in relationship with, the Center for Disease Control came out with a research last year that said if you're born a girl child in the United States, you have a one in two chance of being sexually assaulted.

the women we know, one of women in our family, one of women we work with. and it's men who are beating and raping these women. And that many men could not be beating and raping this many women without widespread cultural support.

How do we change these cultural norms to stop it before it starts?

Rachelle Smith (05:49)

it's just this reality that we have to face that is baked into our culture, like you said, and our military service, it's like 1 % of Americans serve. we're in this.

much smaller environment where these behaviors become readily apparent. But when you're in basic training and they're putting all the military values in you it's honor, it's integrity, it's look out for the person on your left and right, it's, protecting people. it just somehow does not translate once you

get to tech school or your duty station and some people they don't even get to the part where they get the values and basic like they're just trying to take their ASVAB and go to MEPS and the unthinkable happens to them. even just a few weekends ago. I was sexually assaulted again and

I didn't even realize it. I went to a VFW in, Tampa area, let's say. I walked in, wolf whistles immediately, that sorts of stuff. the commander of the place was like, well, you know how they are. I paid the sponsorship fee and he gave me a tour

the men that were catcalling when I walked in, were leaving. the VFW is a big bar, so everybody in there is drinking. he was showing me a mural outside and we were walking back around and these two men were like, are you coming back? yeah, sure, I'll be back. Like, didn't think anything of that. And one man just looks me up and down, undressing me with his eyeballs. he says, well, I'll be in the front

I didn't know what to say to that. So I just didn't say anything. I go inside, the commander's apologizing profusely. he's just saying, you set off a lot of people when you walked in here. I was like, I set off. Okay. so I sit with another young woman and

she's sharing stories about all the people in there. My boyfriend gets done with work most of them think he's my husband and I'm not gonna correct them at this point. maybe if someone shows ownership over me, they'll leave me alone, which is frustrating. another man comes over and he has this big blue Trump hat on.

He's like, what service are you in? And I like, Air Force. And he goes, sister, and gives me a big hug, which was expected. people are very familial when it comes to their particular service. that part wasn't sexual assault. It was the kiss on the neck that followed when he saw that my boyfriend was ordering. then it was the second kiss on the neck that happened again, maybe 15 minutes later when my boyfriend was turned.

speaking to someone else. in that moment, I'm like, okay, do I push this person to the ground and make a scene? Or do I just leave it alone because I'm in here to do outreach for my podcast. I went with the latter the commander saw the second one and he took my boyfriend and I on a

tour of the place again, just to get us away from that individual and he's apologizing the whole time. that happened on a Sunday and on Tuesday, cause it was Labor Day weekend, told my coworker about it and she's a Navy veteran. And she was like, Rachelle, you just got sexually assaulted again. And it was like,

holy shit, you're right. it did not even register to me that that had happened until someone else pointed it out to me because I think I've been so desensitized to adjust from being re-traumatized so many times.

I was able to process it But the funny thing was, was last week I ran into the young woman that I was sitting next to at the VFW She was actually sitting two seats behind me at a baseball game and she texted me and she introduced me to the group of folks she was with. she was saying let's say this guy's name was Dale.

She was like, yeah, we were doing our best to keep Dale away from her. that made me look at her funny because if you know someone behaves like this frequently enough, why are they still here? But that is our entire military culture. And then that is our entire, entire global culture. And that's infuriating.

Chuck Derry (10:09)

And when you're in a culture like, a sexist culture like this,

Rachelle Smith (10:09)

Mm-hmm.

Chuck Derry (10:13)

we can get away with a lot of things.

Rachelle Smith (10:15)

but I do want what this 24 week program was like for.

the men that had to participate.

Chuck Derry (10:22)

they were ordered to participate and they had to acknowledge and accept responsibility for their violence. And you're familiar with the power and control wheel from Duluth? the hub is power and control and then the rubber on the wheel is sexual and domestic violence. there's all kinds of

intimidation, emotional abuse, et cetera, et we would have the men have to log out all the different ways that they abuse Both physical, one week, and then next week would be how to use intimidation. The next week would be how to use emotional abuse, and they'd have to come back and we'd have discussions, and then we'd just go on that way. Now, the thing about it too is that the men were very resistant, right?

minimize, deny, and blame

we first started working with batterers in 80s, we thought, oh, these guys just didn't have the life skills they need to address their emotions, or they lost control, And then we find out we'd be teaching life skills, and they'd use those life skills as a more sophisticated way to control her. the women in Duluth, Minnesota came out with the power and control Victims talking about their reality.

And that's when we realized this is very conscious behavior. They know exactly what they're doing.

so it was interesting to facilitate that group.

the first time I asked the guys in group, I said, guys, so tell me, what are the benefits of your violence? And they all kind of looked at each other, which was really notable, right? Well, and one guy said, there are no benefits. I said, well, you must be something out of it. Otherwise, why would you do it? looked at each other again, and then one guy started talking about the benefits.

and then they all start talking. And then I filled a four foot by eight foot blackboard of all the benefits of their violence and we ran out of space. first time I did that, I looked at that board, I said, my God, Why would you give it up?

Rachelle Smith (12:07)

I do have the article that you had written about writing down

the benefits that were on the four foot walls. I wanted to read a few of she won't argue. She'll get out of your way so that you can go out. You can get money, keeps the relationship going because she's too scared to leave, power, don't have to change for her, total control and decision making.

She's scared and can't confront me. She's an object. Bragging rights. If she works, I get her money. Or I can get her to quit so she can take care of the house. She's a nursemaid. Supper on the table. Don't have to listen to her complaints for not letting her know stuff. She works for me. I don't have to help out. And it goes on and on and on.

with what you said, like, who would give that up? Who really would? it's incredible to see it all lined up like that. How did it feel writing one thing after on the board like that when these men were being open and honest for once?

Chuck Derry (12:59)

Yeah.

Oh it was amazing most amazing thing is we ran out of space on a four foot by eight foot blackboard that's the most amazing they were still going and we didn't have any more space to write down there were so many benefits it blew me away the first time I did it and still every time I'm looking at

I get to dictate reality. I answer to nobody, do what I want, when I want, with who I want. Anyway, the first time writing it down, was just like, my God. I was so happy that they were sharing it. I was so happy that they were being honest about it. So that was Because it really clarified. why men hang on to sexism, men who are not abusive.

they don't want to give up the sexism because they have to give up some the benefits could just be like telling a joke about a woman's body, like what I like to do to it, right? Or anti-woman stuff. And there's a lot of male bonding that goes on around sexual objectification

of women and anti-woman,

But if we had a man who was in week 16 of 24-week program, and he was still denying his violence and still blaming her and minimizing it, we would kick him out of the group. And we had agreements with the criminal justice system, with probation and the prosecutors, that if he was kicked out, he would do some jail time, because he'd have time hanging over his head.

then they send him back to the same group so he couldn't manipulate a new facilitator. Had to come back to the same group same facilitator so they'd leave they do ten days they come back and they'd be there for us week six week eight and they're taking full responsibility for their violence fully acknowledging and not blaming her and i'd ask 'em so tell me jim what what happened

What's going on? when you were here before, were just denying it blaming her all the time, and now you're just taking full responsibility. How come? He said, because I know I can't get away with it anymore.

after man after man. 10 years. I know I can't get away with it because he was being held accountable by the criminal justice system. And that's because the St. Cloud Intervention Project was holding them accountable as well. Because we would track and monitor every case. We wrote policies that they had to sign, right? So they're liable. So the prosecutors, sheriff, police chief, probation.

judges, everything. we were able to track and monitor. then I knew if kicked a guy out in week 16, he's coming back. Every time they said, because I know I can't get away with it anymore. And so that was a key point.

I thought, okay, I'm gonna ask them, okay guys, why would you give it up? And we filled a one foot by one foot space. I got arrested, orders for protection.

My adult children won't invite me to their weddings anymore and I have to come to groups like this. that was when I fully, fully understood the benefits of this violence and how important consequences are. has to be accountability and part of that accountability is consequences. again, like I said, the guys come back and say, I know I can't get away with it anymore.

Does that answer your question?

Rachelle Smith (16:19)

absolutely because my goal with this podcast is to end the problem sexual trauma. accountability is the solution. that just seems to keep getting sidestepped.

year after year. So to hear that coming from an expert, like, hello, military, if you're listening, because they're very big on performative things, we signed the white ribbon pledge and we had a stand down day and we're doing more briefings or first time airmen

joining the Air Force and getting to their first base. They're like, well, they had like a SARC briefing where they talked about emotions and boundaries and this and that. but where is the accountability piece? Where are the people going to prison? Where is the punishment? recently a two star general was charged with a number of things from, sexual harassment, flying while drunk.

⁓ all sorts of stuff. They got him guilty on everything, but actually sexually assaulting a lieutenant colonel. she was coerced because she was like, I can't, this, person's as far above me in the rank structure. So obviously that's not consent, but the military, even though it's in black and white in the, uniform code of military justice, the

people that are, I forget what they call the jurors in a court martial, but every single one of them has a different definition of what consent is. And that changes the outcome when someone has committed a crime.

Chuck Derry (17:46)

Yeah.

And so we have to hold them accountable and provide consequences. And we also have to do primary prevention.

a lot of times people think you gotta raise awareness on men to get them to change. I was 17 years Northwestern Minnesota in a town of 2500, Roseau, Minnesota, 10 miles south of Canada, and the women's libs was going on then This is 1973. And I thought to myself for the first time, I'm 17, I had long hair, what are the few...

dozen guys in town had long hair in those days. I thought to myself, Chuck, what would it mean to you personally if men and women were really equal? And within two minutes I had the answer. I'd have to give some stuff up. Then I thought, nah, I don't think so. And I was a nice guy. And now I had more aware to what a good deal it was in a sexist culture to be a man because we are so benefited.

Rachelle Smith (18:30)

Mm.

Chuck Derry (18:42)

And so that's part of it when working with abusers. Are you willing to give up the benefits? And working with men in general, that was a big challenge for me doing this work. Am I willing to give up all the benefits I have, all the privileges I have being a white guy, but being a man? Am I willing to give up those privileges? And the privileges I can't give up, am I willing to use those to undermine sexism?

Rachelle Smith (19:02)

moments of reflection and then truly understanding where your values lie are so important your development as a human being, whether you're going to be an all right kind of human being or someone that actually has empathy and understands there's a whole world outside of yourself.

Chuck Derry (19:19)

had to go,

am I willing to stop that bonding? Am I willing to confront my male friends and my brothers,

Chances are I'm gonna lose a friend or two if I confront them about telling sexist jokes. come on, we're just kidding around. Yeah, it's fun. We're taking our pleasure at women's pain. And am I willing to stop using porn? Am I willing to stop going to strip clubs? Am I willing to listen? Listen to women. Am I willing to take leadership from women? In a job place, if men and women are really equal, I'm not getting the next advancement. If I have to compete with all the women,

And then all the folks of color as well, I'm not getting into next advancement because now I just have to compete with the white guys. Am I willing even to give that up, right? Do I care about people's lives or not? Because that's what it comes down to.

hey Chuck, who do you want to be? What kind of human being do you want to be?

References

Derry, C. (1994). The Gender Violence Institute. https://www.genderviolenceinstitute.org

The Duluth Model. (n.d.). FAQs About the Wheels. Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs. https://www.theduluthmodel.org/wheels/faqs-about-the-wheels/

Greenburg, J. (2024). Sexual Assault in the U.S. Military. Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Brown University. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/2024/sexualassault

Pence, E., & Paymar, M. (1993). Education Groups for Men Who Batter: The Duluth Model. Springer Publishing Company.

U.S. Department of Defense. (2024). Annual Report on Sexual Assault in the Military: Fiscal Year 2024